Expectations

Expectation is mean in the simplest sense. But what is mean, in probability theory?

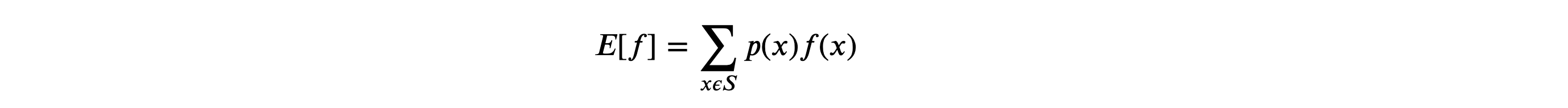

Mean in probability theory or Expectation of any random variable is the weighted average of the probability distribution function of that random variable. Let’s suppose, we have a random variable, 𝑓(𝑥) , which has a sample space of 𝑆 , then the expectation of random variable, 𝑓(𝑥) is given by:

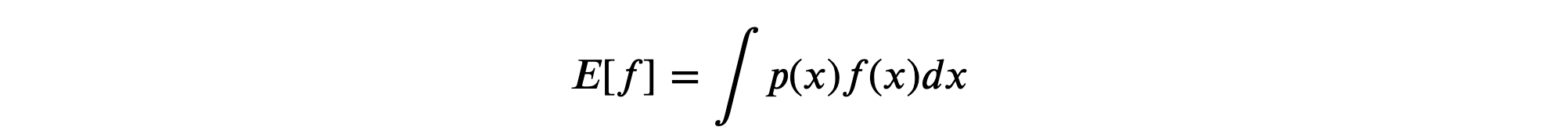

In the discrete distribution, the average is weighted by the relative probabilities of the different values of a random variable. In the case of a continuous random variable, we just replace sum by an integral, and the expression for expectation or average or mean of a continuous random variable becomes:

For instance, let’s suppose 𝑆 is the set of total gym participants in a gym hall, and we select a person uniformly at random. Let 𝑓(𝑥) be the selected participant’s weight Then, the expected value, 𝐸[𝑓] is the average weight in that gym hall. This average value is of great importance in our daily life. Just imagine, you are in a gym and the first thing you want to know would be your weight relative to the average weight of the gym attendees. Thus, it is essential to know the expected value of a random variable.

Uniform Random Variable - Expectation In the earlier section, Probability Distribution Function, we learned that rolling a fair die is a uniform probability distribution since the probability of getting each of the six sides is uniform in every roll. We will use this discrete uniform probability distribution function and calculate its expectation.

##Sample Space

S = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

# probabilities of each of the possible values of random variable

p = {1 : 1/6,

2 : 1/6,

3 : 1/6,

4 : 1/6,

5 : 1/6,

6 : 1/6

}

Expectation = 0

for x in S:

Expectation+=x*p[x]

print(f"The Expectation of the fair rolling die is: {Expectation}")

Output: The Expectation of the fair rolling die is: 3.5

So, the average of the rolling die, which came out to be 3.5 can be quite confusing, but let’s interpret this. If you roll the die a bunch of times and take the average (by summing the values you get and dividing by the number of rolls), the number is going to be close to 3.5. The more rolls you make, the closer the value is likely to be to exactly 3.5. The Law of the Large Numbers says that if you have infinite number of rolls, the actual average comes very very close to 3.5.

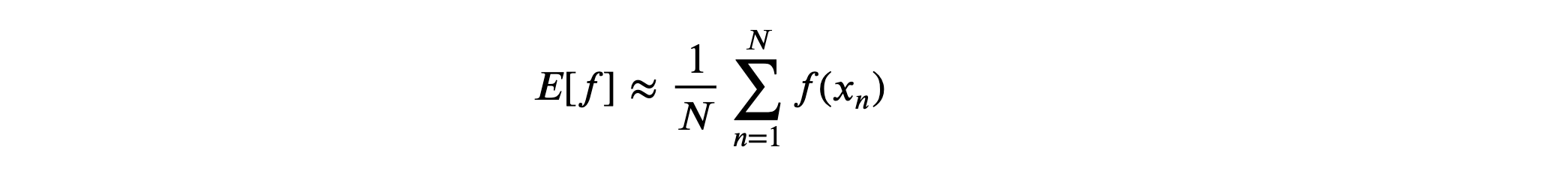

In many cases, we are given the finite number, 𝑁 of points, drawn from probability distribution or density, then the expectation can be in approximation be written as:

And remember, from the law of the large numbers, if 𝑁→∞ , the expectation calculated becomes equal instead of approximation.

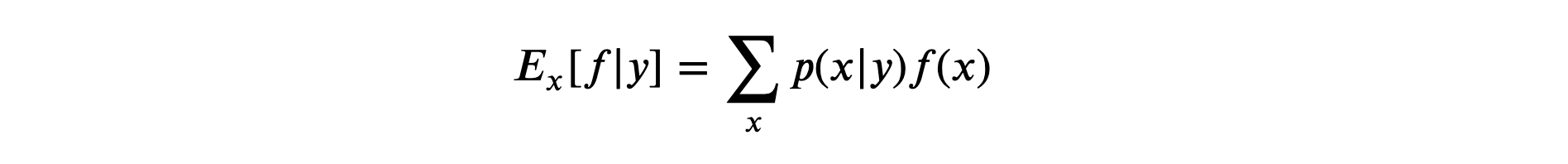

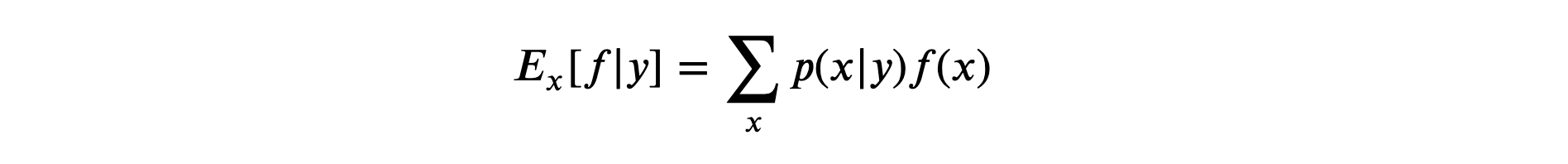

Conditional Expectation We just saw the event probabilities that were conditioned on no events. Now, we will see, conditional expectation where the expectation of a random variable, 𝑓(𝑥) is conditioned on event 𝑌 .

In words, expectation of 𝑓(𝑥) conditioned on an event 𝑌 is the probability weighted, average values of 𝑓(𝑥) over the outcomes of 𝑌 .

For example, Conditional expectation is when we compute the expected value of a roll of a fair die, given, that the rolled number is greater than 2 .

Variance To state in the proper steps, we calculate variance, first, we calculate the difference between each point and the mean, and secondly, we square them, and lastly, we calculate the average of the squared terms, which is called the variance.

Mathematically, the variance of the random variable, 𝑓(𝑥) is defined by:

Variance provides us a measure of how much variability there is in 𝑓(𝑥) around its mean value, i.e., 𝐸(𝑓(𝑥)).

Comments